by Heather Rockwood, Communications Manager

John Adams (JA) and John Quincy Adams (JQA) were fascinated by the hottest flight invention of the 1780s: hot air balloons. Their fascination rivals present-day Parisian’s enjoyment of the Olympic and Paralympic cauldron. Paris citizens are currently collecting signatures to keep the Olympic and Paralympic cauldron as a permanent display representing the French national motto, “Liberté, Egalité, Fraternité.” Since this Olympic flame uses no fossil fuels, only water and light, it could possibly be on display long term.

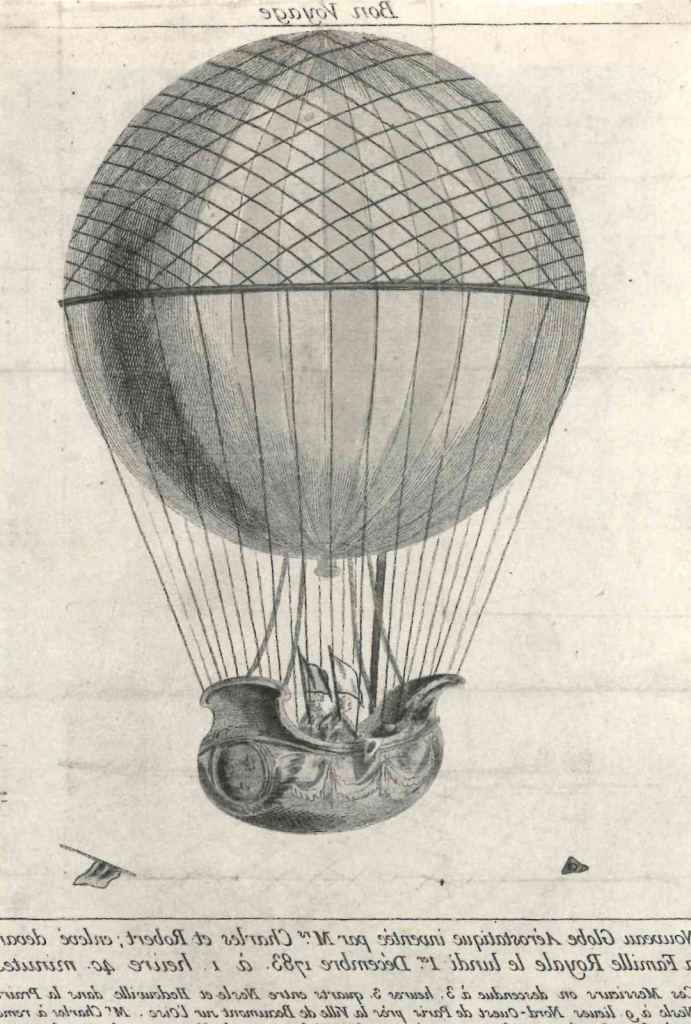

JA and JQA were in Paris in 1783 when Joseph Michel and Jacques Etienne Montgolfier developed their “aerostatique” hot air balloons. These flight experiments caught the fancy of Parisians and the Adamses. On 27 August 1783, JQA wrote in his diary:

“after dinner I went to see the experiment, of the flying globe. A Mr: Montgolfier of late has discovered that, if one fills a ball with inflammable air, much lighter than common air, the ball of itself will go up to an immense height of itself. This was the first publick experiment of it. at Paris. a Subscription was opened some time agone and filled at once for making a globe; it was of taffeta glued together with gum, and lined with parchment: filled with inflammable air: it was of a spherical form; and was 14 foot size in Diameter. it was placed in the Champ de Mars. at 5. o’clock 2. great guns fired from the Ecole Militaire, were the signal given for its going, it rose at once, for some time perpendicular, and then slanted. the weather, was unluckily very Cloudy, so that in less than 2. minutes it was out of sight: it went up very regularly and with a great swiftness. as soon as it was out of sight. 2. more cannon were fired from the Ecole Militaire to announce it. this discovery is a very important one, and if it succeeds it may become very useful to mankind.”

Although this wasn’t the first experiment of flight with the balloon, which occurred 4 June 1783, this was the first public exhibition of it. JA wrote to Abigail Adams on 7 September 1783, “The Moment I hear of it [AA’s arrival in Europe], I will fly with Post Horses to receive you at least, and if the Ballon, Should be carried to such Perfection in the mean time as to give Mankind the safe navigation of the Air, I will fly in one of them at the Rate of thirty Knots an hour.”

This fascination continued and spread! On 10 November 1784, JQA wrote to his friend Peter Jay Munro:

“Messieurs Roberts made their third experiment, the 19th of September, and with more success than any aerostatic travellers have had before. They went up from the Thuileries, amidst a concourse of I suppose 10,000 persons. At noon, and at forty minutes past six in the Evening they descended at Beuory in Artois fifty leagues from Paris. This is expeditious travelling, and I heartily wish they would bring balloons to such a perfection, as that I might go to N. York, Philadelphia, or Boston in five days time. M.M. Roberts have publish’d a whole Volume of Observations upon their Voyage, or Journey or whatever it may be called, but I judge from the abstracts I have seen of it that they have taken a few traveller’s Licenses, and have given some little play to their Imaginations. . . . They have established somewhere in Paris, a machine which they call une tour aërostatique where for a small price, any curious person may mount as high as he pleases, and so ‘look down upon the pendent world.’ ”

On 21 January 1785, JQA dined at Thomas Jefferson’s house in Paris and he wrote in his diary the story of the flight Dr. John Jeffries had taken earlier that month: “Mr. Blanchard cross’d from Dover to Calais in an air balloon, the 7th. of the month. accompanied by Dr: Jefferies. they were obliged to throw over their cloathes to lighten their balloon. Mr: Blanchard met with a very flattering reception at Calais, and at Paris…. All that has as yet been done relative to this discovery, is the work of the French. Montgolfier. Pilâtre de Rozier, & Blanchard, will go down, hand in hand to Posterity.”

The French enthusiasm for ballooning waned after a major accident in June 1785 when aeronauts Pilâtre de Rozier and Dr. Pierre Ange Romain crashed their balloon on the French shore while attempting to cross the English Channel. Their aéro-Montgolfier, a gas double balloon, exploded over a thousand feet in the air and the two fell to their gruesome deaths. On the 23 June 1785, Abigail Adams 2nd wrote to her cousin Lucy Cranch, “You talk of comeing to see us in a Balloon. Why my Dear as Americans sometimes are capable of as imprudent and unadvised things as any other People perhaps, I think it but Prudent to advise you against it. There has lately a most terible accident taken place by a Balloons taking fire in the Air in which were two Men. Both of them were killed by their fall, and there limbs exceedingly Broken. Indeed the account is dreadfull. I confess I have no partiallity for them in any way.”

Like the Eiffel Tower, created to be a temporary exhibition piece for the 1889 World Expo in Paris, I do hope the Olympic and Paralympic cauldron becomes a permanent display.